Hanon or Schmitt?

Many piano students have often regarded the exercises of Hanon and Schmitt as virtually interchangeable. Was one publisher copying the other? Well, to some degree, the answer is “yes”.

Before Hanon published his famous The Virtuoso Pianist in 60 Exercises in 1873, Aloys Schmitt had already published his Preparatory Exercises for the Piano opus 16, fifty-three years earlier in 1820. When we compare the two works, it becomes clear that Hanon looked to Schmitt’s publication as a template for his own. In fact, Hanon directly ‘borrowed' some of Schmitt’s ‘five-finger’ exercises for his collection.

Before Hanon entered the music scene, piano students throughout Europe practiced Schmitt’s Preparatory Exercises during his lifetime. Franz Liszt told Aloys Schmitt that his etudes were part of his technical training in his youth, along with those of his teacher, Carl Czerny. Although Schmitt’s concert music is seldom performed today, his Preparatory Exercises are still used by piano teachers and their students worldwide.

Comparing Schmitt with Hanon

Schmitt benefited from a comprehensive music education and went on to build a distinguished career performing widely across Europe as a pianist, conductor, and composer of four piano concertos, several piano quartets and trios, as well as four operas, two oratorios, and many works for solo piano. Among Schmitt's students was the successful composer, Ferdinand Hiller.

By contrast, Hanon’s education is unknown, and there are no records of him giving public performances or teaching successful students. As an amateur church organist in Boulogne-sur-Mer in northern France, Hanon was deeply attached to a Roman Catholic monastic order, the Brothers of the Christian Schools, founded in the 17th century by Saint John Baptist de la Salle. His primary musical interest was not the piano, but creating organ accompaniments to plainchant for religious services. With so little biographical information available, Hanon remains a somewhat vague figure.

Hanon’s instruction manual for organ students was soundly rejected by professional organists as inept, and his various compositions demonstrate a lack of imagination and found no popularity with the public. However, through the widespread acceptance of The Virtuoso Pianist, Hanon’s worldly success as a self-made publisher was substantial.

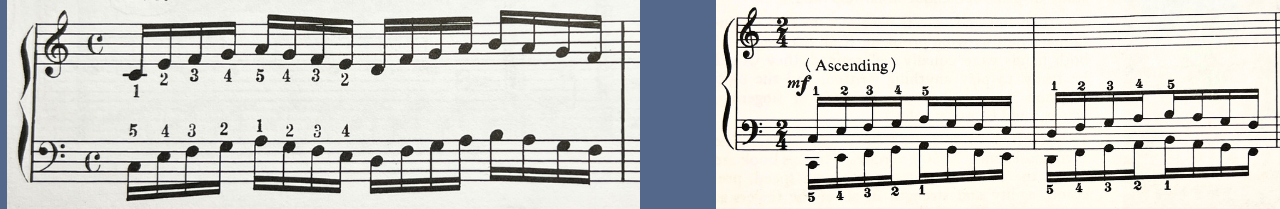

Both Schmitt’s and Hanon’s publications provide examples of ‘five-finger’ exercises that use all five fingers of both hands in repetitive cycles. The aim was to help elementary-level students build their technical skills, especially articulation, elasticity, and velocity, in preparation for more challenging repertoire.

Left image: Aloys Schmitt’s five-finger exercise example. Right image, Hanon’s use of Schmitt’s exercise.

Both volumes illustrate scales, arpeggios, and a variety of musical configurations commonly used in piano music. In The Virtuoso Pianist, Hanon provides fully written-out etude examples, which may make it easier to follow than Schmitt’s volume, which usually offers only abbreviated practice examples.

A key difference between the two volumes is that Schmitt provides ‘held note’ exercises, where certain fingers keep one or two notes pressed while other fingers move independently in sixteenth-note groups. Although effective, these exercises can be very frustrating for beginner pianists, which may explain why Hanon, attentive to pleasing potential buyers, leaves out any examples of this type.

Schmitt Example; notes D and F held down by fingers 2 and 4, while exercising fingers 1, 3, and 5.

The Hanon Controversy

Hanon’s “The Virtuoso Pianist” has been criticized for its questionable practice instructions to the reader in the Introduction and throughout the volume. For instance, Hanon writes in the Introduction, “They [exercises] are arranged so that in each successive exercise, the fingers are rested from the fatigue caused by the previous one.” As any pianist who casually plays through these exercises realizes, no such ‘rest’ is given. Hanon continues, “The result of this is that all technical difficulties are easily executed and the fingers attain an astonishing facility.”

Hanon further asserts, “The entire book can be played through in one hour, and if, after it has been thoroughly mastered, it can be repeated daily for a while, all difficulties will disappear, and that beautiful, clear, clean execution will have been acquired which is the secret of distinguished artists”.

Having taught piano for over 35 years, I would never advise any student to practice Hanon’s entire volume nonstop for a solid hour (and I know of no professional piano teacher who would endorse Hanon’s instruction) since unrelenting exertion is the shortcut to repetitive-stress injury.

As any experienced pianist realizes, the etudes of Chopin and Liszt, and most of the advanced piano repertoire, are never ‘easily’ executed. Many works successfully performed will remain a continuing challenge even for the most advanced concert pianists.

Hanon’s extravagant claims lead me to question whether he had ever personally mastered the advanced piano repertoire. Had he done so, it’s doubtful he would have printed the statements found in his Introduction.

And yet, Hanon’s background and the tone of his proclamations seem not deliberately dishonest, but the naive assertions of an enthusiastic dilettante eager to convert readers into buyers. And he succeeded; his volume was an instant bestseller throughout Europe, and later in the United States, and was widely accepted in music conservatories.

It is ironic that the most popular book addressing piano technique, The Virtuoso Pianist in 60 Exercises, was published not by a concert pianist or pedagogue of distinction, but by a reclusive church organist of limited musical culture and no performing experience.

Putting aside Hanon’s questionable practice recommendations, The Virtuoso Pianist is nevertheless a handy resource for standard fingerings of scales, arpeggios, and a variety of other configurations.

For ambitious students determined to achieve a higher level of technical mastery, I encourage a thorough cross-referencing of Schmitt’s and Hanon’s volumes to identify which exercises may be useful for ongoing technical development.